What if science is becoming toxic to human society?

In the summer of 1950, Nobel-winning nuclear physicist Enrico Fermi didn’t understand the scale of the cosmos as we understand it today. But he knew that it was at least hundreds of millions of light-years across, encompassing thousands of galaxies and more than a trillion stellar systems. Unless Earth was a vanishingly rare exception, the universe should be teeming with life-forms, whose civilizations often would be far more advanced than ours.

And yet, as he asked his lunchmates at Los Alamos one day that summer, “where is everybody?” ET visitations to Earth seemed either absent entirely, or—even if some might be marked by UFO sightings—impossible to pin down as such. This discrepancy between the theoretical abundance of ETs and their observed scarcity or elusiveness became known as the Fermi Paradox.

Ponderers of this supposed conundrum have devised dozens if not hundreds of potential solutions. The most popular, unsurprisingly, are those that echo contemporary human concerns over climate change, nuclear war, rogue AI, etc., positing that such self-made disasters—and maybe also natural disasters like asteroid strikes and supervolcano eruptions—tend to extinguish civilizations before they can reach the star-faring stage. Elon Musk has made clear that he worries deeply about such hazards and hopes to minimize their impacts by making humans “multiplanetary,” for example by colonizing Mars.

The popular, accident-centered conjectures explaining the Fermi Paradox generally assume that in the absence of such cataclysms, civilizations will continue to advance scientifically and technologically, eventually venturing out to the stars. This premise also underlies the contemporary talk of a science- and tech-driven “Golden Age,” in which space travel will become routine.

But what if civilizations normally do not continue to advance beyond a stage of very limited and local space travel? What if the very process of scientific advancement in understanding the cosmos creates a toxic byproduct, analogous to pollutants from industrialization but psychological rather than chemical, such that people inevitably lose the will to explore that cosmos—and ultimately can survive only by regressing to static, relatively pre-scientific social forms?

A Bizarre Conceit

Although at first this might come across as unhinged doomerism, the idea that at least some important parts of science are psychologically toxic is an old and somewhat respectable one. Humans, plausibly as a condition of their civilization-building dynamism, tend to cling to a worldview in which they are very intelligent and special, there is higher “meaning” and “purpose” to their existence, and the universe is somehow about them. As philosophers have been pointing out for hundreds of years, science’s most consistent theme has been the refutation of this grandiose self-image: ”dissuading man from his former respect for himself, as if this had been nothing but a piece of bizarre conceit,” in the words of Nietzsche, who certainly did consider this a bizarre conceit:

However high mankind may have evolved – and perhaps at the end it will stand even lower than at the beginning! – it cannot pass over into a higher order, as little as the ant and the earwig can at the end of its ‘earthly course’ rise up to kinship with God and eternal life. The becoming drags the has-been along behind it: why should an exception to this eternal spectacle be made on behalf of some little star or for any little species upon it! Away with such sentimentalities!

But can humanity survive without such sentimentalities, as science smashes them one by one?

It’s a tough question to answer, since it concerns an influence that probably works mostly beneath conscious awareness, in a psychosocial environment that is complex, to put it mildly. But one thing that seems obviously true of pretension-puncturing scientific discoveries is that they can take generations to “sink in.” Even evolutionary theory, which was already broadly accepted by scientists more than 150 years ago, does not yet seem to have fully replaced our ancient picture of ourselves as creatures made in God’s image. That delay may be attributable to powerful mechanisms of “denial,” to simple ignorance of science, to the residual competing influence of religion, and presumably also to various other socioeconomic factors that tend to counter or crowd out existential questions.

In any case, scientific advances that can create such “existential dissonance” tend to be relatively recent developments on the human timeline. Neuroscience’s refutation of our “free will” illusion occurred only in the last two decades, so unsurprisingly it has hardly begun to be assimilated into our self-image and our moral structures.

Among the sciences, cosmology is plausibly the greatest producer of existential dissonance, and in that sense its influence too has developed only recently. While it is often said that Copernicus demoted us from the center of the universe in the 1500s, his theory was not as revolutionary as it is commonly portrayed. The traditional, pre-Copernican model of the cosmos held that the Earth with its God-chosen beings lay at the center of existence, while all else revolved around it. Copernicus’s model made just one change, putting our sun at the center, which allowed a simpler, more elegant account of celestial motions even as it kept our stellar system in its place of supreme privilege. Thus, a fundamentally anthropocentric view of the universe continued to dominate cosmology—and as late as a century ago, astronomers still believed that the cosmos was very small and tidy, consisting of just our galaxy, with our solar system at or near the center.

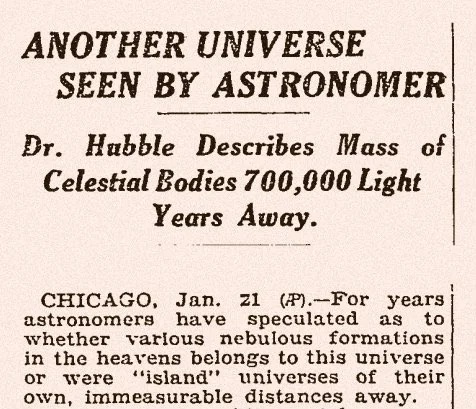

It was only with the development, in the 1920s, of better techniques for measuring stellar distances that astronomers finally understood that the universe was much, much larger, consisting of multiple galaxies, among which ours held no special status—just as our Sun, in a spiral arm far from the Milky Way’s center, held no special status among its galactic peers.

That was a major change. Even so, when I was coming of age a half-century later, the scale of the universe still seemed somewhat manageable. Like millions of other children, I watched Carl Sagan’s Cosmos documentary series in the early 1980s, learning that the universe contains not just a handful of galaxies but at least tens of thousands of them, yet I wouldn’t say that that put an irreparable dent in my belief in human potential. It still seemed conceivable that mankind, with exponentially improving scientific knowledge and technology, could spread outward and someday comprehend—maybe even “conquer”—it all.

The expansion of our cosmic model was still just getting started, though. By the turn of the millennium, with the help of tools like the Hubble Telescope, standard models assumed billions of galaxies. Astronomers also were starting to use the term “observable universe” to delineate the space their telescopes could reach, which, despite its vastness, was apparently incomplete. Indeed, they increasingly embraced the idea that the universe is ever-expanding, and is not just tens or hundreds of billions of light years across but infinite—in all dimensions, presumably including dimensions we can’t perceive.

In a truly infinite cosmos, any local reality would have essentially identical variants elsewhere: “parallel worlds.” As physicist Brian Greene put it in his 2011 book The Hidden Reality, “I find it both curious and compelling that numerous developments in physics, if followed sufficiently far, bump into some variation on the parallel-universe theme.”

MWI

The best-known and most widely held parallel-world theory these days is the “Many Worlds Interpretation” (MWI), initially devised by Hugh Everett III (1930-1982) in the mid-1950s while he was a physics PhD student under John Wheeler at Princeton. Everett’s work was mostly ignored while he was alive, though other physicists, notably Bryce DeWitt and David Deutsch, did much to popularize it later among physicists and the general public—and to extend it and give it its present name.

MWI is called an “interpretation” because it tries to make sense of a conundrum at the heart of quantum mechanics: In certain types of experiment, any quantum-scale particle such as an electron or a photon seems to possess an innate multiplicity. In other words, it manifests as a ghostly ensemble of particles (with different positions and velocities) and only when an experimenter tries to detect it more directly does it stop acting like a ghostly ensemble and resolve to just one particle. The leading interpretation in quantum mechanics’ first half-century or so was that this “collapse” to just one state is induced by the experimenter’s act of observation, and that the other, left-behind states are somehow not real. Everett proposed instead that all these states are real and essentially represent different versions of the particle that end up being captured—by different versions of the experimenter—in different universes. In short, MWI holds that reality consists of multiple universes, in which, collectively, anything that can happen does happen.

Everett’s idea was rejected at first, as new ideas that threaten the status quo and its defenders typically are. But the reaction to MWI wasn’t just the usual circling of the wagons by the old guard. Even many who admired the theory’s elegance were discomfited by it. As Oxford philosopher of physics Simon Saunders said to a reporter in 2007, “The multiverse will drive you crazy if you really think about how it affects your life, and I can’t live like that. I’ll just accept Everett and then think about something else, to save my sanity.”

Still, MWI was and remains elegant and consistent with experimental results. As alternative interpretations of quantum mechanics have fallen by the wayside, it has risen steadily in popularity, not just among physicists but also among science popularizers—and popular audiences, as suggested by the success of the MWI-themed 2023 movie Everything Everywhere All at Once.

MWI recently received further support when Google reported a “quantum supremacy” demonstration by its experimental quantum computer Willow. A feat of quantum supremacy is a feat that a quantum computer—whose computational bits exist not as discrete 0 or 1 bits but in ghostly superpositions of both—can achieve that an ordinary “classical” computer can never match. It is regarded as an empirical proof that quantum computing is real, which for many physicists also bolsters the validity of MWI, because the idea of quantum computing—first developed by Deutsch in the mid 1980s—is that such computers gain their advantage in effect by performing computations across different universes.

—from Google Quantum AI blog post 9 Dec 2024

A Concealed Toxicity

The scientific and technical elites who have brought us these developments have been, at best, silent about their implications, and at worst, actively deceptive—although maybe they have been deceiving themselves too. As I was rewatching Cosmos (1980) recently, I noticed it was now prefaced by Ann Druyan, Sagan’s widow and a writer and director on the series, who invokes the “soaring spiritual high” of science’s “central revelation: our oneness with the universe.” Essentially every mainstream author or commentator on cosmology has had similarly upbeat things to say—about the beauty of the universe, and/or the cleverness of humans in their recent leaps of discovery. This is not just self-deception—these experts have to sell books and other media content, and publishers want positive themes.

But it is all deceptive. Why? Because, again, science’s central revelation—cosmology’s especially—is the insignificance of humanity, and for MWI and other infinite-cosmos theories this is not just a relative insignificance but an absolute, one-over-infinity insignificance.

The MWI cosmos is, in a technical sense, more splendid and elegant than anything found in human religion. What could be more perfect, what could be more complete, than an infinitude in which everything that can happen does happen? The problem is that this perfect completeness, or maybe unendingness, leaves no room for “purpose,” “meaning,” or “achievement” in any substantive sense. It also mocks our childish notion that we could somehow explore and/or “conquer” it all.

In fact, MWI implies that there is no higher purpose or meaning to any human being’s actions or existence, other than by filling out, in an infinitesimal way, the infinite space of possibility. Are you a good person in this universe? Are you “successful”? How can this be substantially meaningful (from the perspective of a Creator who transcends the multiverse), if otherwise indistinguishable variants of you are bad and unsuccessful in other universes—and presumably average to a mediocrity across all instances? When you combine this “MWI view” with the modern neuroscientific view of behavior—as being determined moment-to-moment by innumerable, mostly subconscious factors while our conscious selves stand by as purblind spectators—you start to get a picture of humans as “non-player-character” (NPC) automata in a sort of video game with infinite parallel playthroughs.

To the extent that people see themselves and their lives from this perspective, they are likely to lose a lot of their motivations for doing things—and not just the great and ambitious things but also the ordinary, pro-social behaviors that keep societies from coming unglued. Such behaviors are rooted in concepts of good and bad, meaning and purpose, and MWI erodes all that as completely as would a revelation that we live in a simulation.

MWI defies our traditional self-image so starkly and extensively that it also calls into question the “sapiens sapiens” label we have given ourselves. Perhaps, when compared to other civ-building species in our galaxy, we aren’t very smart at all. Perhaps our simple ape brains are already nearing the limits of what they can do—limits that fall well short of what even the most basic star-faring endeavors require.

Signs of Despair

Again, big changes in our understanding of our place in the cosmos can take generations to sink in, and MWI and other infinite-cosmos notions began seeping into the popular mind only recently. It may be that only children born in this millennium are being—and have been—forced to confront these ideas in a substantial way during the impressionable years when their models of the world and moral structures come together. If so, it may take another decade or two for this particular form of despair to be recognized as a mass phenomenon, distinguishable from all the other forms of despair out there.

In the meantime, despair is undoubtedly prevalent in our materially prosperous civilization, particularly among the young. “Adolescent mental health continues to worsen” reads a recent CDC headline, over a story that notes that in 2023 about 40% of American students had “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness.” A commission set up by Lancet Psychiatry issued a report last summer concluding that “in many countries, the mental health of young people has been declining over the past two decades, signalling a warning that global megatrends and changes in many societies are increasing mental ill health.” Whatever is driving this pandemic of despair and depression seems also to be promoting “nihilism” and “doomerism” among the same youthful demographic.

While this putative trend may be attributable mostly to other social and economic disruptions of recent decades—from electronic media overexposure to the high cost of family formation—perhaps some is being driven by science, which after all has been moving in the same direction, displacing religiously based beliefs and ethics, for centuries now. In any case, despair caused by other factors is treatable in principle, whereas the one served up by science seems incurable.

One of my premises here is that the people who built Western civilization couldn’t have done so without believing, at least subconciously, that there is (or probably is) meaning and purpose in life and the universe. If so, then removing that sense of meaning and purpose would likely remove that civ-building dynamism our ancestors had, and the only way to recover meaning and purpose—perhaps the only way for humans to survive, in the long-term—would be to renounce and suppress most science and technology and revert to more primitive social forms.

One would expect to see this cultural arrest and regress play out first in the Western societies that have been the most diligent in jettisoning religion. And indeed, the essentially post-Christian societies of Northwestern Europe now look pretty moribund in most respects compared to their peers; certainly, they lack the “ad astra” energy of the contemporary USA.

The current hoopla over AI raises the question: Couldn’t we create advanced robots and robotic starships that self-replicate and relentlessly explore outer space, without regard for the apparent pointlessness of the endeavor—in fact, without any emotion at all? Yes, in principle, if we could remain motivated long enough to develop the necessary AI and robotics tech. But autonomous robot exploration is not the same as human exploration. Moreover, it’s not hard to imagine these clever creations eventually finishing off their depressed, listless, impotent creators, in a perfect and final example of a “cure” that kills the patient.

The idea that cosmology and other key branches of science eventually become toxic to a technological society offers a solution to Fermi’s Paradox because it is plausible that not only humans but also other intelligent species that emerge in the cosmos and start venturing into space face this same problem—this fundamental conflict between, on the one hand, the self-delusions needed for basic civilization-building and progress, and on the other, the delusion-bursting science needed to reach the stars.

Incidentally, cosmology’s hint about our relative inferiority as a species suggests another, complementary solution: The few star-faring civs that do exist in our vicinity either do not care about us, or, even if they are curious enough to visit, don’t waste time trying to communicate—firstly because we are too primitive to process what they would have to say, and secondly because almost anything they could convey, particularly regarding the nature of the cosmos, would injure us.

***