Thoughts on tauromaquia.

Originally published 20 July 2016

About a hundred fair Julys ago—it seems that long anyway—I ran with the bulls in Pamplona.

If you’d asked me why back then, I would have said simply that it seemed a fun thing to do, a thrill, an “experience” to tick off a tourist’s list. It would have felt silly to describe it as a chance to prove one’s courage. But I think that is mainly what it was.

We bull-runners were all men or boys. Nearly all of us wore the traditional uniform of the encierro (thin white cotton shirt, red bandanna). Many of us also carried a rolled-up newspaper, said to be useful for distracting the bull with a swat to the hindquarters if he happened to be goring a friend.

A rocket went off and burst to warn us as the first bulls were released from a pen into the zigzag course of the town’s narrow streets. The animals had to pound down a lane and round a corner before they encountered most of the human runners who waited for them.

Now here they came. Who knew how fast those half-ton monsters moved? We runners lurched forward, with the twin fears of injury on the one hand and cowardice on the other. To avoid both, it certainly helped to be in a group. Running alone, becoming the sole target of all those horned beasts, was almost inconceivable. But there was danger too in being amid a jostling pack: many runners stumbled and fell with, it seemed, too little time to rise and evade what approached with such inhuman speed.

And suddenly that first group of bulls and steers rumbled by, all hooves and bulk and undulant muscle. Like most of the runners, I had managed to get to one side of the narrow, cobblestoned street to let them pass. Some other runners, though, were caught in the middle and sent sprawling. A miraculous few stayed up, jogging gamely, as the great beasts missed them by inches.

I ran again, found daylight, heard the next pack coming, let them pass, and just managed to sprint into the plaza de toros before the last bulls entered and the gate closed behind them.

To my surprise, if no one else’s, a series of younger bulls was then let out to confront the few dozen of us who had made it into the bullring. One of the first animals took aim at a German tourist—a scruffy-looking character, borracho and slow—and chased him down easily, driving him face-first into the dirt. The guy might well have been killed, had the young bull’s horns not been padded. Later the same animal, chasing one of us, leapt over the plaza’s barrera and raced around forcing panicked bullring staff and spectators to spill into the comparative safety of the bullring itself. We runners laughed with relief as we took a breather, but soon were eager for the next novillo toro to be let out so that this primal test of our courage could start again.

At the time it seemed a forgiving test. It was clear that tourists in the encierro, especially the drunk ones, were routinely gored or trampled, but I assumed that truly serious or fatal injuries were very rare. There wasn’t yet an Internet with which one could immediately check such statistics. Even at the real bullfights, in the afternoons at Pamplona, where the bulls were injured and maddened and vengeful, the matadors appeared to be in little danger; one of them kept such a cautious distance between the bull’s horns and his own costumed hide that the spectators began to hurl insults—maricón! el peor!—and even seat cushions into the ring.

However, some Spanish bullfighters were reputed to be very skillful and brave. Among them was Jose Cubero (“El Yiyo”) Sanchez. Later that summer, in southwestern France, I saw posters listing him in the lineup for a corrida to be held in Bayonne in September.

Alas, Sanchez didn’t make it to Bayonne, or even to September. On the 30th of August, in Madrid, he was nearing the end of a seemingly routine bout when he attempted the ritual sword-thrust, which is meant to go into the bull’s upper back and thence downward through the heart. He missed. The angry bull turned, charged, upended the matador, and—as the 21-year old tried to scramble away on all fours—stuck him with his left horn in the upper back. In full view of a large crowd, the bull lifted Sanchez completely off his feet so that he slid down the horn until his own heart was pierced.

Having done his work, the bull let the man go. Sanchez ran just a few steps before collapsing, famously gasping his last words, “este toro me ha matado,” as they rushed him in vain to the ring infirmary.

Those memories came back last week when I read about the unfortunate Victor Barrio, the first matador to die in the bullring since Sanchez.

It happened at a late-night corrida in Teruel. Towards the end of a fight with a bull called Lorenzo, Barrio goaded the bleeding, wary animal to charge the cape. The bull at last did as he was bidden, but as Barrio swiveled for the next pass, Lorenzo without warning shifted his attention from cape to matador—some later spoke of an unlucky, cape-lifting gust of wind—and with an upthrusting left horn to the back of the knee the bull sent his human tormentor leaping evasively into the air.

It was a relatively minor goring, but the bull was not finished. The moment the matador hit the dirt, Lorenzo, using the same left horn, began trying to stab him in the chest. Barrio started to roll away but Lorenzo quickly hooked him below the right arm and, hopping on front hooves to make full use of his 529-kg weight, drove the horn most of the way through the man’s chest cavity.

Lorenzo then jerked the embedded horn sideways for good measure, destroying Barrio’s right lung and thoracic aorta among other things, and violently lifting his body off the ground. When, just about six seconds after making that first sudden stab to the leg, Lorenzo flung his conquered adversary off his horn, the 29-year old matador had only enough time to pull his arm over the wound in his side and roll over, face down, before darkness overcame him. He died in full view of the crowd, his eyes opening sightlessly, his muscles relaxing into the flaccidity that in traditional societies marks the release of the soul to heaven.

In bullfights, incidentally, that is the ideal ending: the killer’s thrust swiftly stops the victim’s heart. Perhaps no bull has ever turned the tables as perfectly as Lorenzo.

And Lorenzo as far as I know had never practiced fighting humans. Like the brother taurus that killed Sanchez, he seemed to know from long-evolved instinct to use his horns to maximum effect by going, when he could, for his antagonist’s chest. As any hunter or soldier will tell you, the chest of a mammal is the prime kill zone, easily hit and especially vulnerable to mortal wounds.

In the plaza de toros at Teruel that night, it all happened too quickly for the spectators to process. Barrio had been gored somehow and was down—that was obvious. But there was no visible gush of blood. That this was because his heart had almost immediately been stopped was unimaginable. The man had been standing, smoothly handling the bull with his cape just a few moments before. His young wife, though she was seated even closer to the action than most other spectators, assumed her husband’s wounds couldn’t be fatal.

“I was saying to myself, ‘It’s serious but he’s going to survive, he’s been gored, but nowadays no-one dies from being gored, there’ll be a solution.

**

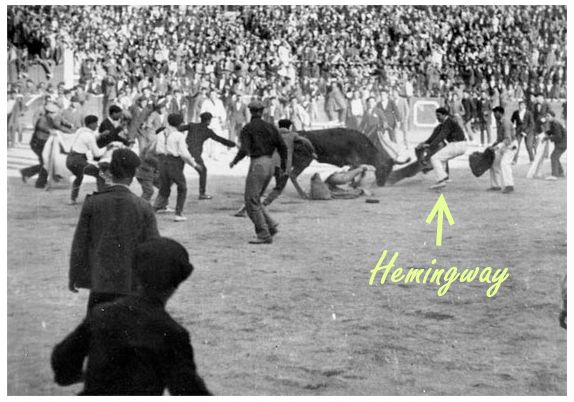

No one dies? What then would be the point? As Hemingway observed, “Bullfighting is the only art in which the artist is in danger of death.”

Barrio and Sanchez surely knew that—knew about the danger, at least, even if they also knew that bullfighting doesn’t always rise to the level of art.

Alas, these days, talk of danger and art are mostly lost on the audience beyond the bullring. The bien pensants of social media heaped scorn on Barrio and bullfighting in response to the story of his death.

Even in Spain, the rapid modern shifts in customs—largely driven, as elsewhere, by the cultural ascendancy of women—have meant that bullfighting is treated more and more as a bloody relic of a barbarous past.

Bullfighting is undeniably cruel, and sometimes can seem irredeemably so. At Pamplona all those years ago, I saw one bull killed in a most unsporting way, which was nevertheless common: The swords had all missed so that the matador, amid the crowd’s jeers, had finally to sever the poor kneeling animal’s spinal cord with a dagger to put it out of its misery. And still the bloody travesty continued: When they tried to hook the bull’s carcass to a team of horses that would drag it from the ring, someone slapped the horses prematurely, before the attachment was made. The horses sprinted forward, unloaded and out of control, until the one on the far right smashed against the edge of the arena’s exit, and was left writhing on the ground with serious injuries. Someone then had to come out and put it out of its misery, with a pistol if memory serves. It seemed a horrible waste—though almost incredibly it was much worse a century ago, when the picadors’ horses went unpadded and were often gored so badly that their intestines spilled out and dragged on the sand behind them.

And yet I can’t join the anti-tauromaquian chorus. I’m not a Spaniard and I’m generally loath to criticize other cultures—to each his own, I’m inclined to say. More specifically I think bullfighting is too ancient, and potentially too beneficial, to just throw away.

Bullfighting is many things. It is for example a drama—Hemingway called it a tragedy—symbolizing the eternal contest between man and beast: brains vs. brawn. Plausibly it also represents the higher, more hopeful struggle of mankind vs. its own mortality.

Most straightforwardly, though, bullfighting is a highly ritualized, indeed professionalized elaboration of simple, prove-your-courage-with-a-deadly-beast displays—displays that are still largely preserved in the public encierros at Pamplona and other Spanish towns, but that date back to prehistoric times. Ancient Mediterranean cultures are suffused with themes involving bulls and men, typically in conflict. The most famous surviving artifacts of the early bronze-age Minoan culture, of roughly 3,500 years ago, feature very encierro-like “bull leaping” activities.

Arguably the basic meme of man vs. bull dates back all the way to humans’ earliest surviving narrative tale, the Epic of Gilgamesh, which is about 4,000 years old.

The Bull seemed indestructible, for hours they fought, till Gilgamesh dancing in front of the Bull, lured it with his tunic and bright weapons, and Enkidu thrust his sword, deep into the Bull’s neck, and killed it.

There is little in this rich history to suggest that bullfighting, or even the bull-running and bull-teasing of encierros, have as their aim the “torture” of beasts for perverse enjoyment, or the competition of “sport,” or even the attainment of “artistry.” All those can be (and generally are) realized in other ways that are much less dangerous to the practitioner.

It is that danger, that risk of grave injury or death, and the simple, primal manifestation of that risk in a powerful animal, that makes bullfighting and related amateur activities unique. One social benefit is that it teaches men the possibility of courage in themselves; it glorifies that courage as something worth having; and it evokes the ancient past in which such courage was utterly necessary.

Is courage so valueless these days that we can afford to part with practices that encourage it? How could we ever be sure?

**

If bullfighting statistics are any guide, then we the men of the West—considering matadors as our proxies—are losing our courage. More than 500 professional bullfighters have been killed in the ring since 1700, but only a handful of those deaths have occurred in the last half-century. Better medical care for wounded matadors and an improving economy (which makes bullfighting less attractive as a career choice) have something to do with that discrepancy, but surely not everything.

Another factor seems to be that matadors are on average less willing to work in close proximity to bulls—that has been part of aficionados’ litany for much of the past century, as the great names of bulfighting’s heyday have faded into memory. There have also been, it is said, more of the shady tricks that weaken bulls before they get to the ring. Among these is horn-shaving, a practice that Hemingway described thusly:

To protect the leading matadors, the bulls’ horns had been cut off at the points and then shaved and filed down so that they looked like real horns. But they were as tender at the points as a fingernail that has been cut to the quick and if the bull could be made to bang them against the planks of the barrera, they would hurt so that he would be careful about hitting anything else. . .

Even Manolete, often considered the greatest matador of all time, was sometimes protected this way. In the 1930s and 40s his bullfights brought in so much revenue that he became an industry in his own right—and that industry didn’t want to lose its key man.

But if Manolete’s reputation suffered a bit from the shaving, his fatal goring in 1947 redeemed it. Late in an August bout at Linares, boldly reaching over the bull’s head to drive in a sword, the 30-year old matador was nicked by a horn in his groin and began bleeding badly from his femoral artery. The bloodstain spread quickly down his left leg.

Manolete nevertheless stayed up, kept the bull working, and finally, with the animal close to death, limped away and was carried to the infirmary.

As he lay in the infirmary, Manolete lit a cigarette and asked in a weak voice, “Is the bull dead?” After being informed that the bull was, indeed, dead, Manolete said that he could not feel his legs.

These days he would have survived such an injury, but his ultimate reputation would have suffered: his decline and death would have been more drawn-out, and certainly less interesting. As it was, Manolete (whose real surname was Sanchez) died of his injury the next morning, and passed into everlasting glory.

Juan Belmonte (1892-1962), the other greatest-ever matador, may have envied Manolete’s end. Belmonte despite a long career and many serious gorings retired safely, and, it seemed, lived a life not unlike that of the rare fighting bull that is spared death and put out to stud. He bought a ranch and raised horses on it, and was rich. But he kept un-retiring and resuming bullfighting again, and being injured again, and retiring again, and then un-retiring, and so on as if nothing else in life measured up to the fundamental challenge of the bullring.

Eventually in 1962, when Belmonte was 70 and in failing health, his doctor advised him to stop riding horses and performing other manly exertions. According to the dressed-up legend, which in a cultural sense may be more revealing than the facts, the old matador went defiantly out to his ranch, indulged one last time in horse-riding, cigar-smoking, drinking, and sex with a pair of young women, and then—like his late pal Hemingway—shot himself, there being no bull, or matador, available to take his life for him.