What is the true cause of American Performative Violence?

On a recent Saturday in always-sunny Palm Springs, California, a 25-year-old who could have been your son or mine drove his car into a parking lot behind a fertility clinic and set off a homemade bomb within the car, in an effort to obliterate the clinic and himself. The first media report I saw gave me the impression that the bomb was not very big, as the people in the clinic were only injured. In fact, the device was remarkably powerful, nearly destroying the low concrete clinic structure despite detonating five to ten meters away, and throwing pieces of the car—and of its driver—blocks away. It seems to have been the largest bomb built for such a purpose since 1995, when Timothy McVeigh used a 7,000-lb truck-borne fertilizer bomb to destroy the ten-story Federal building in downtown Oklahoma City.

The bomber of the Palm Springs fertility clinic, whose name was Guy Edward Bartkus, shared some important characteristics with McVeigh. He was young, male, and girlfriend-less. He was fascinated by things that go bang—explosives and incendiaries in his case. He felt alienated from modern society and hated its trends. He was functional but showed at least mild signs of mental illness. He seemed to have found a cause for which he was willing to die—and kill.

The particular cause that Guy Bartkus embraced might seem a parody of Internet-nurtured extremism were it not for the tragedy it engendered. Bartkus described himself, in online writings and a recorded manifesto before the attack, as a “pro-mortalist.” He hated being alive, believed that life brought only suffering, and held, moreover, that birth itself was wrong because the unborn could not consent to being born—thus his targeting of an IVF clinic.

Some media organizations fastened on this “pro-mortalist” theme in the days following the blast, declaring for example that there were “fears the movement may be on the rise.” Of course, there was and remains no real evidence of a substantial movement of pro-mortalists. In the world of the always-online can be found every half-baked idea and ideology imaginable—if you can imagine it, someone will have posted about it somewhere—but it is rare that any of these mutant mindsets results in an organized social malignancy. Why? Probably because the people who are captured by these fringe beliefs tend to lack the necessary social skills.

Still, while there may be no real pro-mortalist movement as yet, I can’t help wondering if the appearance of this unusual worldview in the ongoing story of American Performative Violence (my term for it) offers a useful hint about what is driving this story—a hint that reminds us of the deficiencies of the standard expert explanation.

The standard expert explanation for the acts of the Bartkuses and McVeighs is that they are lonely, resentful, mentally friable and socially inept males, usually young ones, whose crime would never have occurred but for American society’s libertarian laxity. In regard to the latter, the experts—in every big-publisher book on this subject—specifically blame weak restrictions on access to large-magazine firearms and bomb-making materials, weak restrictions on violence-inducing Internet content, and inadequate law-enforcement and social-services monitoring.

Since the experts’ prescriptions appear to require gun laws that violate the Constitution, as well as a police-state-like surveillance of citizens and restriction of Internet content, they haven’t been adopted to the degree needed to be effective. Thus, the problem continues to fester, even as the expert view of it remains unchallenged.

*

The idea I would like to introduce here is that the expert opinion and “received wisdom” on the causes of this type of violence place far too much emphasis on policy shortcomings, and far too little emphasis on cultural shortcomings—especially the loss of identity, social connection, and the overall sense of meaning and contentment.

First, though, some caveats and clarifications: The spectacular mass killings (actual or attempted) at issue here are distinct from the stealthier, one-by-one murders of “serial killers” such as Jeffrey Dahmer and Ted Bundy. The latter represent a comparable problem for law enforcement and public safety, but these men (rarely women) are, in a sense, psychopathic killers we will always have with us. They are not exclusive to modern technological societies—think of Jack the Ripper—nor even to the First World; the serial murderer Luis Garavito killed hundreds of young boys in Colombia in the 1990s, for example.

Moreover, mass shootings/bombings/stabbings/car-rammings and so on have two non-policy-mediated causes or inspirations that everyone already acknowledges, namely 1) militant Islam, for a subset of Muslim perpetrators; and 2) simple “monkey-see-monkey-do” imitation of acts that reliably (albeit mostly posthumously) bring fame/notoriety. Both are recent cultural developments—militant Islam is largely a reaction to modern secularizing influences and trends, while the imitative aspect of these crimes is enabled and enhanced by modern globalized electronic media and especially the Internet.

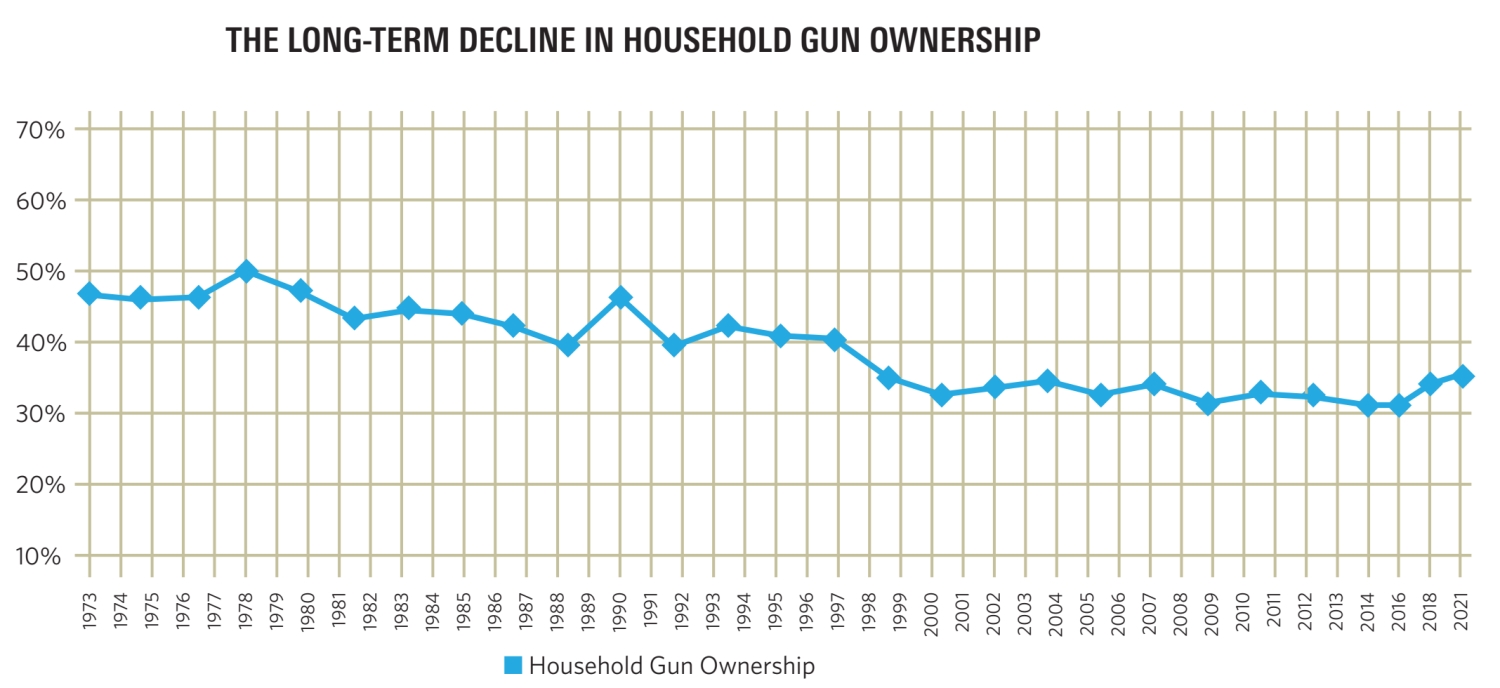

We should look to recent cultural developments for the causes and inspirations of American Performative Violence for the simple reason that it represents, at least in its frequency and intensity, a new social phenomenon. For the same reason, we should give less weight to policy-related explanations: American gun laws were much looser, and gun ownership per household much higher, in the mid 20th century when these performative or “rampage” mass killings were still very rare[1].

In relation to these killings, I expect the most important difference between the mid-20th century and the present is the difference in the overall health and structural integrity of American society. I could reel off a hundred sets of statistics, but probably the most relevant facts are that the US population in the pre-performative-violence era was mostly based on two-parent families, was relatively religious and churchgoing, was relatively socially interconnected, and (not counting African-Americans, who were sequestered by the apartheid system of the day) was racially and ethnically homogeneous. Most Americans, in short, had healthy and intact senses of identity, meaning, purpose and social rootedness in 1950—whereas a lot fewer have all that three quarters of a century later.

When people don’t have these things, they become more susceptible to despair, even if they are not consciously aware of it. And within any large population affected by despair, the most unstable and disconnected ones will be the first to “snap.” How will they snap? Mostly by killing only themselves—directly with a gun or pills or homemade noose, or indirectly through food, drink, and/or dangerous recreational drugs. Only a tiny minority, acutely affected by a compulsion to redeem their sense of uselessness, will opt for performative murder-suicide—a paradigm that the culture in effect has chosen for them. As loathsome as these murderers of the innocent may seem, their deaths too are “deaths of despair.”

*

The underlying problem therefore is not loose gun policy any more than it is loose “knife policy” that causes contemporary mass stabbings, or loose “car policy” that causes the increasingly common practice of driving cars murderously through crowds. Unfortunately, the roots of this cultural problem lie so deep that there probably isn’t any policy in a contemporary, democratic Western society that could solve it.

Western—and even “Western-adjacent”—societies have been going through rapid cultural, structural and demographic changes. These changes have multiple drivers, including the socially atomizing “technologicization” and related power of corporations in virtually every domain of ordinary life; the historically sudden establishment of parity or dominance by women in virtually all institutions and organizations [link]; and the strong rejection—as a concession to the fait accompli of mass immigration—of the old ethnonationalist basis for societies in favor of the new “contractual” or “free agent” model [link].

The new Western model of society, is, in short, an emasculated, polyglot conglomeration of lonely—and mostly childless—consumers, relatively bereft of any sense of identity or social connectedness, or even any stake in the future. The God that once animated this Western civilization and its feats died long ago, or switched to being some sort of not-very-effectual personal therapist.

Arguably the hardest problem here, though it may be the most neglected, is that the comforting cosmological sense of place that religion once provided has been left to science. If you listen to cosmology popularizers supported by the contemporary publishing industry, or to a high-profile space nerd like Elon Musk, the main message of science is that the universe, vast and wondrous, beckons us to explore it—so that maybe we shall even “become one with it” someday. However, if you ignore all the hopium and the book-selling propaganda, you may begin to grasp what the discoveries of science over the past few hundred years really have been telling us. This message, not such a nice one, is that we are, most likely, in comparison to the complexity of the universe and the development of its older entities, much as ants or even bacteria are to the human world. To grasp this, one doesn’t even have to believe in an infinite universe or an infinite multiverse of parallel universes—but once those potent concepts and the evidence for their reality are also grasped, it becomes hard to ignore the likelihood that our lives, our hopes, our moral systems, our efforts to invent “meaning,” are all incurably naïve, even delusional.

And, of course, once that dark reality is glimpsed, even unconsciously, inhibitions against antisocial behavior of all kinds will tend to be weakened.

In this view, then, American Performative Violence belongs in a broader category that I suggest could be termed “Positive Despair” because it features positive, or added, symptoms and behaviors—in this case, mass-murdering violence—in comparison to what is normal. If I am right, the incidences of this and other manifestations of social and existential despair are going to keep rising, increasingly blurring the line between “sick” and “healthy.”

***

[1] https://en. wikipedia.org/wiki/Howard_Unruh